Food is a basic human right. And the right to food is different than the right to charity.

The theme for the UVM Food Systems Summit in June, which was hosted by the University of Vermont and Vermont Law School was, The Right to Food: Power, Policy & Politics in the 21st Century. The topic was explored from the angles of the biophysical constraints, to feeding the world’s population, to the geopolitical context of the global food system and the implications of behavior and culture. But the clearest description for me, of where we are now and how we got here, came from keynote speaker Raj Patel “Cheap workers need cheap care, need cheap food, need cheap fuel, need cheap nature.” And when industry is asked to solve the problem, they often respond by “putting vitamins in it.” Seriously: Coca Cola Light Plus–soda pop with vitamins.

According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, globally, one in nine people are chronically hungry. And yet we produce more calories now than are required to feed all of the people on Earth.The challenges are of distribution across income, environmental, and technological constraints. Scholars, practitioners, and food system leaders engaged in two days of conversation about how to address these challenges.

According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, globally, one in nine people are chronically hungry. And yet we produce more calories now than are required to feed all of the people on Earth.The challenges are of distribution across income, environmental, and technological constraints. Scholars, practitioners, and food system leaders engaged in two days of conversation about how to address these challenges.

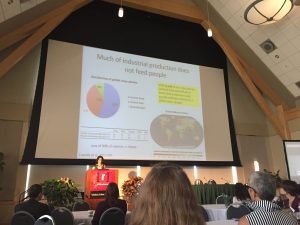

One of those scholars, Claire Kremen, talked about how we feed people in terms of agroecology, saying that what we grow, and how the calories are allocated are important things to keep in mind when we talk about feeding nine billion people, “We absolutely will need to rely on more sustainable methods of farming, including organic farming. Industrialized farming methods that are practiced around much of the world today are not sustainable.”

And from Smita Narula, an attorney and activist “I like talking about food as a human right because it helps to expose the fundamental imbalance of power in our corporate food regime: A handful of agribusinesses exert immense control over and reap tremendous profit from the production, processing, and distribution of our food; while those who produce our food, including small-scale farmers and agricultural laborers, form the majority of the world’s food insecure—most of them women and people of color.”

And from Smita Narula, an attorney and activist “I like talking about food as a human right because it helps to expose the fundamental imbalance of power in our corporate food regime: A handful of agribusinesses exert immense control over and reap tremendous profit from the production, processing, and distribution of our food; while those who produce our food, including small-scale farmers and agricultural laborers, form the majority of the world’s food insecure—most of them women and people of color.”

We also heard from several groups from Vermont, and how they are addressing some of these problems, including Paul Feenan of the Vermont Youth Conservation Corps and how they are growing food for CSA shares prescribed by doctors, and from Ellen Kahler of Vermont Farm to Plate and how New England is planning on producing 50% of its food from the region by 2060.

How many Vermonts fit in…?

How many Vermonts fit in…?